Pablo Policzer, Adam Policzer and Irene Boisier

Pablo Policzer is the director of the Latin American Research Centre and an associate professor of political science at the University of Calgary. A specialist in comparative politics, his research focuses on the evolution of violent conflict in authoritarian and democratic regimes. His book The Rise and Fall of Repression in Chile (Notre Dame University Press, 2009) won the 2010 award for best book in comparative politics from the Canadian Political Science Association. He obtained his PhD in political science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his BA (Honours, First Class) in political science from the University of British Columbia.

Adam Policzer and Irene Boisier met when they studied architecture in Santiago’s Universidad de Chile. They married and had three children. They were active supporters of Salvador Allende’s government. In 1973, the government was overthrown by a military coup. Adam was imprisoned for two years. When he was freed, the family came to Canada. After validating his credentials, Adam opened a private architectural practice, specializing in social housing. Irene, after receiving a master’s in urban planning at UBC, worked as a city planner and later as a community development worker helping marginalized people, mostly immigrants and refugees. At present they are both retired, living in Vancouver.

Pablo’s Story

With an illustrated account by Adam Policzer and Irene Boisier

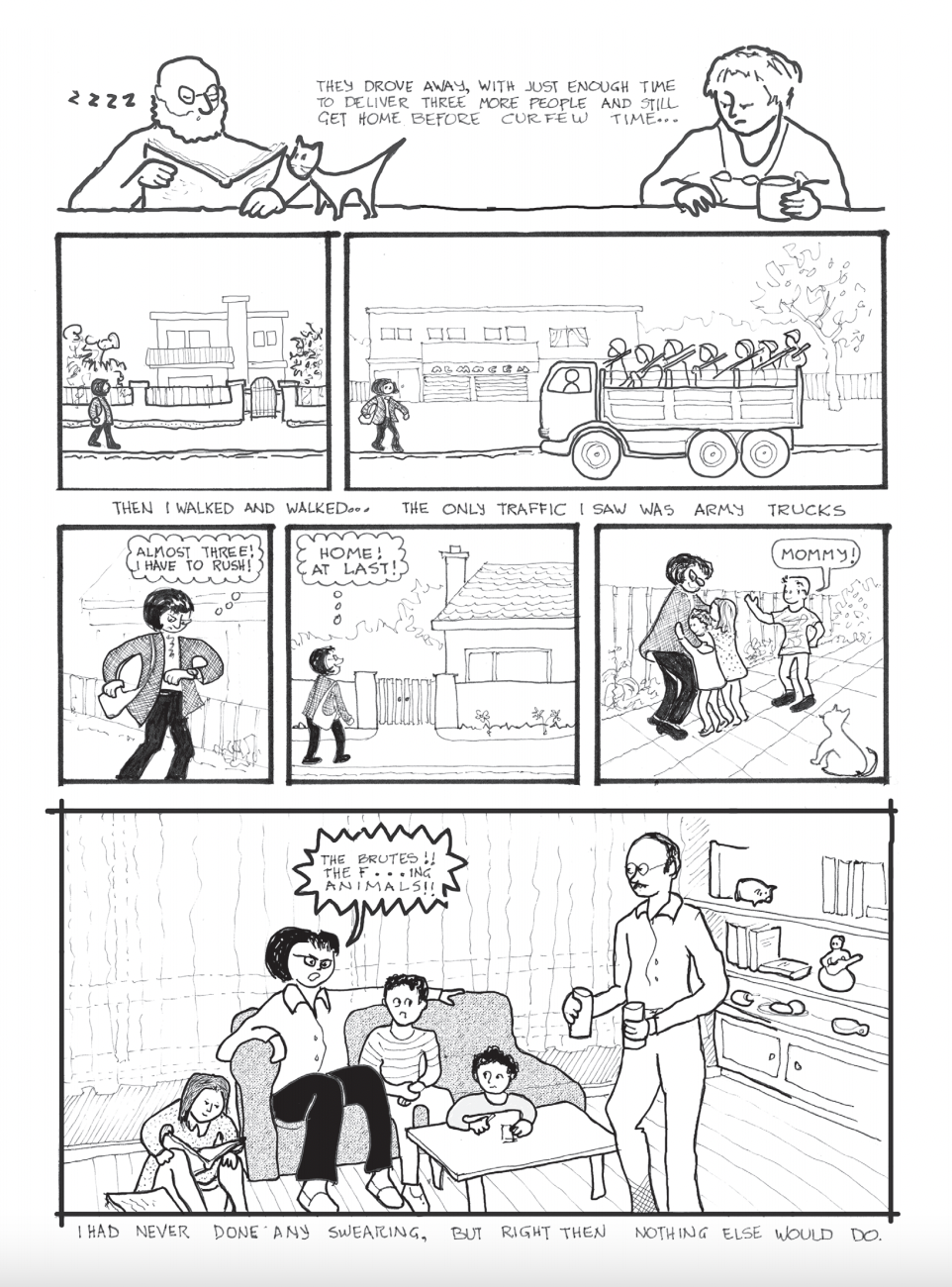

Santiago, Chile, September 11, 1973. It was a Tuesday, and I was eight years old. I listened to the radio that morning in the living room with my sisters and Elena, our nanny. My parents kept us home from school, but they went to work. Or at least they tried to go to work. Dad worked a few blocks from La Moneda, the presidential palace. He heard the bombs fall and smelled the smoke. Mom worked across the street from La Moneda and saw and felt the bombing up close. Each decided to return home instead of staying to put up a futile resistance.

The Chilean armed forces overthrew President Salvador Allende’s government on the morning of September 11, 1973. We heard Allende’s last broadcast over the radio: “The Air Force has bombed . . . history is ours . . .” I didn’t completely understand what was happening, but my parents supported the Allende government and the Socialist revolution it was trying to bring about, and I knew this was serious.

Elena couldn’t hide her own fear, especially because for several hours we didn’t know where my parents were or whether they would make it home. Dad returned first, and then mom several hours later. It would take years for me to understand the consequence for all of us of the decisions they’d made that day. People around them had stashed some weapons in anticipation of the coup, and many decided to use them. Dad, especially, considered joining them, but in the end, he came home. Many of those who held out were killed, many more imprisoned. Years later, I learned that those early days were the deadliest. Many people were brutally tortured and killed with impunity. Had my parents stayed put, our lives would have been different.

Instead dad was arrested a couple of months later, in early December. He had a car—a Citroën 2CV, or “Citroneta”—and drove a friend to the French embassy. The plan was to help him hop the fence to seek asylum. They drove by the embassy and saw that it was guarded by soldiers. They drove by a second time, but no luck. They paused for a smoke and coffee and decided to try one last time. They were stopped. The friend was kicked out of the country a week later, and my father was kept as a political prisoner.

We didn’t know where he was at first, and I remember the tension at home. Mom, my grandparents, all the adults. No one knew, and no one told us. This was an adult problem, and children were kept in the dark. But some kids did know. My friend Daniel, who was a little older than me and whose own father had gone into hiding, teased me about it. Didn’t I know that my dad was in prison? I forced mom to tell me, and she brought me into the secret. She didn’t know much at first, but suspected dad had been taken prisoner. She asked me not to tell my younger sisters, Ana and Catalina, who were six and four at the time. I was still a child, but as the oldest, being entrusted with this heavy secret was a step into the burdens of adulthood. The idea was to protect my sisters by not telling them. Later, as teenagers, each of them would express how bewildering it had been to be kept in the dark about the real reason for dad’s absence.

We began to get some concrete information after about a week. He’d been held by the civilian police force, and then transferred to a detention centre run by the Army in the Estadio Chile, the covered basketball arena downtown. At least he was alive. It must have been weeks later when mom and I went to visit him. He appeared from behind the barriers inside the stadium, walking toward us in a trench coat. I cried with relief, finally seeing him in the flesh.

Again, years later when researching this period, I would learn that dad was fortunate. He wasn’t captured during the brutal chaos in September just after the coup, but also not during early 1974, when a deadly new secret police force would begin to simply make people disappear. Despite disappearing for about a week, he was instead processed in a more bureaucratic way. His name appeared on lists of prisoners. The International Committee of the Red Cross knew where he was, and so did we. It was harder for the regime to kill people others were watching. If he’d been detained a couple of months later, he would most likely have disappeared without a trace.

He spent a year and a half as a political prisoner. First six months in the Estadio Chile, then six months up north in Chacabuco, an abandoned desert mining town converted to a concentration camp, then back near Santiago by the coast for about a month, then under house arrest until he was finally released in June 1975. During this time, mom kept her job as an urban planner in the Ministry of Public Works, now working directly under the military officers in charge. They knew that her husband was in prison, that she was trying to get him released, and that she wanted to leave the country. Trained as an architect, like dad, she also worked overtime to look after his clients while he was in prison. Years later, I would also learn how hard it was for her with the heavy burden of caring for three children and keeping up dad’s practice, while being forced to work for the regime that kept her husband in prison.

My school also changed after the coup. It was a public school with a reputation for being progressive but one day soldiers appeared and took over. Long hair was forbidden, and we had to line up and sing the national anthem in front of the flag every morning. Years later I would learn that some of my teachers were expelled, but at the time I still went to class and played soccer with my friends at recess. The teachers who remained tried to keep things as normal as possible, as did the adults in my family, with birthday parties, Christmas presents, and trips to the seaside. But there was tension and fear. I knew I had to be careful about what I said and to whom. I knew about prisoners and feared I might be detained as well. At home we talked about what to do if soldiers came looking for something or someone. The golden rule was not to say anything. One of the books my parents got rid of shortly after the coup, just in case along with the obviously political ones, was a textbook on reinforced concrete—El hormigón armado. They feared soldiers might misinterpret the title, as armado can also mean “armoured” or “armed.”

I hid under the covers of my parents’ bed, pretending that soldiers were walking by, and practising being perfectly still so they wouldn’t find me. I rode on the back of a friend’s Citroneta, lying on the flat bed, with eyes closed, pretending to be a blindfolded prisoner. Ana and I played a game to figure out only from the movement of the car where they were taking us. When dad was in prison, I regularly woke up in fear, screaming in the middle of the night, convinced that intruders had entered the house. I forced mom to get out of bed to help me look for them. Without dad around, I felt responsible for keeping our home safe.

The adults talked about places like England, France, Australia, Venezuela, and Canada. Mom took us to the Canadian embassy at one point. We knew people who’d emigrated there. The visa to Canada was issued just after dad’s release. We later suspected that an officer in the ministry might have helped mom by facilitating dad’s release, in anticipation of a visa that would take us out of the country. But we don’t know.

The original plan was for all five of us to leave in June, after dad was free and as soon as the visa was issued. But I contracted typhoid fever, and then gave it to Ana. No entry to Canada for sick children. Perhaps no entry for any of us. It took some pleading for Canada to allow dad to travel first, and for the rest of us to follow. At that time Chilean refugees could still choose where to land. My parents consulted their encyclopedia, and saw that Vancouver had the mildest climate. The decision to move to Vancouver—one of the most consequential my family ever took—was based on nothing more complicated than fear of the cold.

We spent about three months apart. My first images of Canada came from a picture book: mountains, forests, snow, and moose. Dad’s letters added new elements: Vancouver had a beautiful downtown park, and there were squirrels and crows. I couldn’t wait to see this new land with exotic animals. Mom, Ana, Catalina, and I left Santiago on September 18, 1975, which was Chilean Independence Day. On the way to the airport we drove past flags and celebrations everywhere. Also soldiers on the street and helicopters overhead. Our dog, Tino, ran after us for many blocks. We learned later that he returned only after several days, emaciated, and died not long after. A part of us also died with him, I think. As the plane rose into the air, I felt relief.

We landed in Vancouver the next morning. Mountains, water, trees, all clean, fresh, modern. Together again, in a new home. One of the first things my parents did was to put me and my sisters in front of the television to watch Sesame Street. “You have to learn English,” they told us. Dad spoke from experience. He’s Jewish, born in Hungary in 1938. He lost his mother and most of his family in the camps during the War and arrived as a seven-year old refugee in Chile in 1946. We were both about the same age when we became refugees, and he knew that the way to survive was to adapt, to integrate. He had become Chilean as a child, and now our task was to become Canadian.

We started school soon after arriving with Ana and Catalina in regular classes and me in an ESL program. There were kids from different parts of the world. I’d never met anyone from India, China, Iran, Germany, or Sweden. We sang songs and played games. I slept well now, with only bits of English intruding into my dreams. In Santiago, once we knew we were going to Canada and would have to learn English, I had trouble imagining what that would be like. Canadians must translate into Spanish, I told my friends, because how could anyone think in any language other than Spanish? Impossible. But about a month after starting school, I caught myself in the playground, thinking in English for the first time. It was easy after that. I still had a lot to learn, but thinking in English without translating made all the difference.

Years later, I came to understand that we were lucky to have landed in Vancouver just as Canada was embracing a new politics of multiculturalism. In recent years there has been more resistance to the arrival of immigrants and refugees, but at the time the message we heard everywhere was “Welcome, you’re a new Canadian.” Yes, we were different, but so was everyone else in a society that embraced those differences. Chileans stuck together, forming associations and organizations to raise money for the resistance against the dictatorship, but we didn’t live apart, in a ghetto. We struggled financially, as my parents worked hard to validate their credentials, study, and find work. But we integrated in school, and after a while my parents landed on their feet. Mom worked in her field as an urban planner and dad in his as an architect. Canada embraced us as we became Canadian.

The community of Chileans in Vancouver was small but tightly knit, even while it reproduced many of the political and class divisions in Chile. A key question was “When did you arrive?” Most Chileans landed after the coup, beginning in early 1974. But a few, wealthier and more conservative, had arrived in 1970, fleeing the newly elected Marxist government. They took their capital out of the country when it elected a government intent on taking over the means of production. I became friends at school with kids from those families. And even among the larger community of refugees from the dictatorship, there were divisions. Years later, as a political scientist, I learned that Chile has one of the strongest party systems in Latin America. As a teenager in Vancouver, I experienced the way Chileans sorted themselves out along party lines, especially Communists versus members of the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, or MIR). Dad had been a member of Salvador Allende’s Socialist Party, and I went to some Socialist events early on, but that fizzled out after a few years. The Communists and the MIR were much better organized, and continued to operate until well into the 1990s, long after the end of the dictatorship. Early on I remember the sense of transgression, going to a Communist or a MIR event. Was it wise to cross those lines? Would working with one party compromise our ability to work with another?

Those partisan distinctions and identities were important at first but began to lose their significance by the end of the dictatorship in the 1980s. The military lost a plebiscite in 1988 that asked the country whether they wanted eight more years of Pinochet. I was in Vancouver’s La Quena coffee house, in many ways the centre of the Chilean exile community, listening with everyone to reports of the results by long distance phone calls from friends in Chile. We celebrated in joyous disbelief that the dictatorship had lost, and that its end was now in sight.

A year later, after graduating from the University of British Columbia with a BA in political science, I was in Chile for the elections in December 1989 and the transfer of power to a new democratic government in March 1990. Living in Chile during that time had a powerful impact on me. I witnessed the transition to democracy up close, attended rallies, and talked to a broad range of people, including political leaders of all stripes, and shared in the pain and joy of the end of the dictatorship. I was hooked and decided to pursue political science as an academic career.

I also began to understand how much I’d been shaped by growing up as a refugee in the exile community. Exile politics are notoriously black and white. Spending almost a year back in Chile, I saw a much more complex society than the strict good exiles versus evil dictatorship stories I’d grown up with. I spent a lot of time with my extended family, the overwhelming majority of whom had supported the dictatorship, even while seeing us suffer through prison and exile. Some lost faith in the dictatorship soon after the coup, as they saw the brutalities it was committing. Yes, they wanted to stop Chile becoming Marxist, but they were shocked by the horrors of repression. Others remained firm in their support of Pinochet. For them, he’d saved the country, and they ignored or discounted his atrocities. There were difficult conversations with relatives who barely knew we existed, let alone why we’d been forced to leave. I saw that we’d been written out of their history, and that my presence was a challenge to narratives they’d come to accept. I understood my role as a painful but necessary part of Chile’s larger process of coming to terms with its past.

My presence forced some in my family to reassess their narratives, and although I didn’t anticipate it, my meeting them began to do the same to me. I came to better understand those who saw the Allende government itself as a threat, who feared that Chile could join the Soviet sphere. I heard stories about how shortly before the coup, the entire family celebrated my uncle’s wedding, which was the last time they were together, before everything broke. The conversation turned to politics, not surprisingly, and the fears of an impending armed confrontation. As supporters of the Allende government, my parents were in the minority. My uncle Sergio, afraid of the slide to Marxism he was witnessing, told me that he asked my father whether he thought force would be needed to defend the revolution. “Of course!” was dad’s response. “At that point,” Sergio told me, “I knew there was no turning back.” If someone like my father, whom he loved and respected, had become convinced that force was the only option, the country was irreparably broken and divided. Sergio feared that force would be used against people like him and his family.

I later asked dad about this conversation. Although he didn’t remember it exactly, he admitted that yes, he most likely had said this. It was a time of division and conflict, and as a young man he had been swept up. He also confided that in some ways he thought we’d been lucky that the coup happened when it did. If the revolution had continued, instead of victims, perhaps a few years later he and so many others might have become victimizers. Thankfully, we’ll never know. I appreciated this frankness, especially from someone who’d been twice victimized, as a Socialist in Chile and as a Jewish child in Europe during the Holocaust.

Hannah Arendt, the political philosopher who wrote much on totalitarianism, knew that under the right circumstances most of us are capable of being complicit in atrocities. It doesn’t take monsters to commit evil. In my middle age I’ve come to appreciate how different circumstances in my childhood might have propelled me and my family down very different paths. The alternative lives we were spared, thankfully, include those without my father, mother, or both. But they also include alternatives without the coup, where a possibly successful revolution might have victimized my extended instead of my immediate family. My parents have always been driven more by compassion than ideology, and they would likely have been among the first to protest the revolution’s excesses instead of lining up to be its victimizers. I’ll never know. But many Chileans who did end up in exile in Eastern Europe were shocked by what they saw and expressed that this was not what they had fought for.

Canada had a history of accepting politically friendly refugees from Communist countries like Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. The Chileans were the first Marxist refugees, and there was resistance at first to admitting politically risky people from across the Cold War divide. I am of course extremely grateful that Canada took a risk in embracing us. But now it’s important for us to bear the heavy burdens of citizenship. That involves, among other things, not perpetuating the myths of refugee victimhood.

Chileans were undoubtedly victimized, like so many other people Canada has admitted. But it’s not hard to imagine an alternative history where the moral valences are reversed. We could easily have walked down very different paths. I think of this when I see the debates today over which refugees to admit and how to properly screen them. Victims yes, victimizers absolutely not. While it’s true that modern wars regularly target innocent civilians, conflicts in places like Syria, Afghanistan, Sudan, Colombia, the Balkans, or elsewhere, don’t sort people out into neat categories. And even though some figures we’ve come to revere, such as Nelson Mandela, at one point advocated violence, any hint of that on the part of a refugee is likely enough to keep them out of the country. My intention here is not to outline a more effective refugee policy. It’s simply to provide a testament that Chilean refugees are as complex and contradictory as anyone. Those complexities and contradictions are not a threat to be avoided, or an embarrassing history to be swept under the rug, but a potential to be better understood. At some point in the future, perhaps, refugees may be able to become citizens without continually demonstrating their victimhood.

Policzer, P., Policzer, A., Boisier, I. (2021). From Chilean Refugee to Canadian Citizen. In G. Melnyk & C. Parker (Eds). Finding Refuge in Canada: Narratives of Dislocation. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press.